Using Pedal Point in a Chord Progression

Pedal point, with regard to chord progressions, refers to the fact that you keep one note constant throughout a progression, even if it doesn’t actually fit the chord. This usually happens in the bass. For example, if you were to play the following progression: C F G C, your bass note will change from C to F to G and back to C.

With a bass pedal point, you’d keep the note C in the bass for all the chords, even though the note doesn’t even exist in one of those chords (the G chord). The notation for that would look like this:

C F/C G/C C

The note after the slash tells us which pitch the bass (or whatever other instrument is playing the lowest-sounding note) should be playing.

Bass pedal points are a great way to breathe a bit of freshness into an otherwise boring, predictable progression. It’s also a good way to help a complex progression sound a bit more acceptable, since the listener will tend to focus on that bass note as a kind of musical “anchor.” For example, play the following progression with the note C in the bass for all chords:

C Ab/C Db/C G/C Ab/C Bb/C C

It’s possible to put the held note in an upper part rather than the bass part. When you do that, it’s called an inverted pedal. For examples of an inverted pedal, listen to the high-pitched guitar in the final verse of The Beatles’ “Back In the U.S.S.R“, and also to the guitar in “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” (The Supremes).

Identifying Chords that Work Well Together

For those of you looking to find out how and why some chords work together while others are more of a problem, check out this article from “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” blog.

The Essential Secrets of Songwriting Blog

Sometimes all you really need is to get some chords that work, and to learn how to add chords to the melodies you’ve written. “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 6-eBook bundle tells you everything you need to know, and gives you hundreds of progressions that will get your songwriting back on track. More..

Sometimes all you really need is to get some chords that work, and to learn how to add chords to the melodies you’ve written. “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 6-eBook bundle tells you everything you need to know, and gives you hundreds of progressions that will get your songwriting back on track. More..

__________ If you are a chords-first kind of songwriter, this has probably happened many times to you: you find a nice couple of chords, like C and Dm. You play them back and forth, but then you wonder: what other chords would go well with those two? Other than random searching with your guitar or keyboard, is there any way to know how and why some chords work so well together while others don’t?

If you are a chords-first kind of songwriter, this has probably happened many times to you: you find a nice couple of chords, like C and Dm. You play them back and forth, but then you wonder: what other chords would go well with those two? Other than random searching with your guitar or keyboard, is there any way to know how and why some chords work so well together while others don’t?

For the vast majority of music you’ll encounter in the pop genres, music is in a key, and identifying that key will tell…

View original post 463 more words

When – and When Not – to Combine Rests in Written Music

The concepts in this blog post refer to Lessons 13 and 14 of the “Easy Music Theory with Gary Ewer” Course.

CLICK to read more.

____________

If you take a glance through printed music, you’ll notice that sometimes you’ll see dotted rests, and sometimes you’ll see several rests in a row, with no dots. There are rules that govern when rests can and/or should be dotted. Here’s a quick overview.

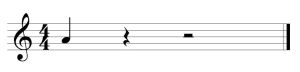

Take a look at the following bar of music written in 4/4 time – a simple time signature:

So which rests can we combine into larger ones? In time signatures that have an even number of beats (2, 4, etc), there is a rule that a rest should not extend beyond the middle of the bar. So it would be incorrect to follow the quarter note with a dotted half rest.

The correct solution is to follow the quarter note with a quarter rest, and then combine the two remaining quarter rests:

By doing this, no rest extends beyond the middle of the bar.

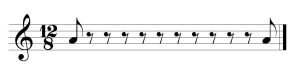

Now let’s look at an example from compound time:

Which rests can be combined, and which ones must be left separate? In any time signature (though it comes up more often in compound time than simple time), rests that finish a beat should remain separate, while rests that start a beat can be combined. When you add that to the rule that rests should not extend beyond the middle of the bar, you get this as a solution:

As you can see, when you properly combine rests, the music becomes more easily readable, which is the whole purpose of music notation.

-Gary Ewer

What Is an ‘Implied’ Chord?

_______________

Get “Easy Music Theory with Gary Ewer” – a complete rudiments course! Available on DVD or as an immediate download.

_______________

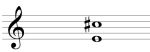

A chord is the simultaneous playing of three or more notes at the same time. As you likely know, we deal mostly with triads in music, which are a specific kind of chord that uses a root, a 3rd and a 5th. For example, when you play a C-major chord, you are playing a triad, a 3-note chord that uses a root (C), a 3rd (E) and a 5th (G).

An implied chord is a term that’s used to refer to a chord that doesn’t use all 3 notes, but still sounds complete enough to “imply” the full chord.

For example, if you play simply the notes C and E together without the G, it will still sound like a C major chord, even with the note G missing.

The issue of implied chords comes up often when discussing songwriting. That’s because in many songs, the producers purposely use implied chords in the first verse. For example, if you listen to Rihanna’s hit song, “Only Girl (in the World)”, the sparseness of the instrumentation at the beginning is a good example of how implied chords are used. Here’s a description of how that works.

In most musical composition, an implied chord is a good way to make music sound quieter. That’s an important part of differentiating between a verse and a chorus, especially if they use the same or similar chord progression.

–Gary Ewer

Is There a Different Kind of Music Theory for Different Musical Instruments?

Music theory is not dependent on the instrument you play. So whether you are a guitarist, pianist, saxophonist, trumpeter, bass player drummer… all music theory is the same.

Having said that, there may be a difference in the way it is taught, and special emphasis might be placed on certain aspects of music theory that depend on your instrument. For example, drummers may place a lot of importance on the study of rhythm. But even that importance may be misplaced: all instrumentalists need to know the theory of rhythm, not just drummers.

Many theory courses use the piano keyboard to demonstrate some musical ideas. But that’s simply because the piano keyboard makes the notes easy to see and refer to. So if you are a trumpeter in the school band, learning the piano keyboard will help you with your understanding of music theory. It’s not necessary to become proficient as a player of the piano, but all instrumentalists should at least be able to identify the notes of a keyboard.

To understand music theory means to understand how music is “built”. Think of this analogy: whether you’re going to build a chicken coop, a garage, or a 4-bedroom house, the basics of “builders’ theory” – how to hammer a nail, how to correctly measure and cut lumber, why buildings stand up with little or no danger of falling down… all builders need to know those things, no matter what they are building.

In the same way, all musicians will benefit from knowing how music works – how it goes together, why it sounds the way it does.

So there is no difference in the kind of music theory you’d learn, no matter what instrument you play. The day you start learning is the day you become a better musician!

–Gary Ewer

Does Music Theory Stifle Creativity?

_______________

Get “Easy Music Theory with Gary Ewer” – a complete rudiments course! Available on DVD or as an immediate download.

_______________

Does studying music theory stifle your sense of creativity? The quick and short answer to this question is: no, of course it doesn’t.

Does studying music theory stifle your sense of creativity? The quick and short answer to this question is: no, of course it doesn’t.

Music theory was never meant to instruct you with regard to composing music. Rather, it is essentially a history lesson for why music sounds the way it does to us. Music theory exists because past musicians have done something so often in music that we’ve come up with a “theory” to explain why it’s done that way, and why it sounds the way it does.

For example, the fact that a C chord is the tonic chord in the key of C major is part of music theory. The fact that songs in the key of C major often end on the tonic note and chord, and sound so satisfying as an end chord, is part of theory as well.

Does that mean that every song we write that’s in the key of C major should end on the tonic note and chord? Of course not. The theory involving the tonic chord simply tries to tell us why that chord works the way it does, and why so many musicians prefer to end C major songs on that chord.

But it does not demand that you do so.

So if you are looking to music theory as a set of instructions for how to compose music, you are totally missing the point. Music theory shows us why music sounds the way it does, why it works the way it does, and for those two reasons alone, becomes tremendously important to students of music.

Think of the study of music theory as the beginning of creativity, not an end.

-Gary Ewer

September 2013 Online Easy Music Theory Quiz

Have you been working away at the “Easy Music Theory” course, and want to test your understanding of the rudiments of music? Here’s a little quiz for you to try. No prizes, just bragging rights! The questions go from easy to difficult. Once you’ve finished, check the answers here.

If you want to brag about your score in the comments below, feel free. But NO GOOGLING the answers! 😉 And obviously, no bragging if you had to look up the answers.

- A flag does what to the length of a note?

- Doubles it.

- Halves it.

- Replaces a dot.

- Makes no change to the length, just makes it pretty.

- A time signature with 6 8-th notes in every bar, where the 8th-notes are beamed in pairs, is:

- 6/8 time.

- 8/6 time.

- 3/4 time.

- 2/4 time.

- The name of the interval represented by a low note of D and a high note of Bb is:

- major 6th.

- minor 6th.

- major 7th.

- minor 7th.

- The name of an interval between a low note of Gb and a high note of G is:

- chromatic semitone.

- demonic semitone.

- diatonic semitone.

- chronologic semitone.

- The pattern of tones and semitones that makes up a natural minor scale is:

- T st T T T st T

- T st T st T T T st

- T T st T T T st

- T st T T st T T

- A compound time signature divides each beat into ____ subdivisions.

- 4.

- 3.

- 2.

- 6.

- The technical name for the 3rd note of a scale is:

- mediant.

- submediant.

- dominant.

- subdominant.

- A triad is a:

- 3-note chord where the 3 notes must be consecutive letter names (e.g., C-D-E)

- 3-note chord, with the only condition being that the 3 notes must belong to the home key. (e.g., C-A-B)

- 3-note chord in which one note is the root, the second is a 3rd higher than the root, and the 3rd note is a 5th higher than the root. (e.g., C-E-G)

- 3-note chord, with no rules as to which notes must be present. (D#-Gb-Bb)

- When a triad is inverted:

- The root is not the bottom note.

- The root is the bottom note.

- The root is always missing.

- The triad contains a dissonance.

- A scale that goes from E to E (an octave higher), using a key signature of 3 sharps, is:

- E Aeolian.

- E harmonic minor

- E mixolydian

- E dorian

END OF TEST – Check your answers here. Have fun! (And don’t forget to post your test results below if you feel like boasting!)

Can Music Theory Make You A Better Songwriter?

_______________

Get “Easy Music Theory with Gary Ewer” – a complete rudiments course! Available on DVD or as an immediate download.

_______________

Some of the benefits of a knowledge of music theory are obvious, including the ability to read and understand other people’s music. But there are other good reasons why an ability to read and write music will help you, particularly if you are a songwriter.

Here’s a list of just a few:

- You can communicate your musical ideas to others more easily. Getting your ideas down on paper (or into a notation software program like Sibelius or Finale) means that you don’t have to keep demonstrating to others what you mean. It’s a way of being absolutely precise about what you’re doing in your song.

- You can write your own background vocal harmonies.

- You can write your own instrumental accompaniments.

- You’re less likely to forget good ideas you had yesterday. Once they’re written down, you’ve got them for good.

- You’re more likely to get interesting gigs. If players know that you read, you’re a safe person to bring in to a gig at the last minute. They can communicate their ideas to you quickly and easily.

- You can jot down music that you hear, and see why it works. Music notation allows you more easily analyze music.

- It expands your musical imagination. Like an ability to read words, reading music opens the world to you in very important ways, and makes it easier for you to be positively influenced by other great songwriters.

-Gary Ewer

Do I Need to Use a Piano to Learn Music Theory?

The concepts in this blog post refer to Lesson 3 of the “Easy Music Theory with Gary Ewer” Course.

CLICK to read more.

____________

In the Easy Music Theory course videos, particularly Lesson 3, I use a piano keyboard to demonstrate some of the concepts. There is one good reason why a piano keyboard is so useful: you can see the notes before they’re played. You can also see the physical relationship between the various notes of scales and chords.

That visual aspect that’s offered by the keyboard makes music theory easier to understand. But that is not to say at all that music theory only really applies to the keyboard.

Nor does it mean that you must learn the notes of the keyboard to properly understand music theory, though it will help. In most music programs at the college level, students are usually required to have some basic piano skills, and in many degree programs, students must study the keyboard.

You don’t need to become proficient at playing a piano, but serious students of music would be well advised to at least be able to name the notes of the keyboard. You will find that it will help with your understanding of music theory, even if your main instrument is clarinet, trumpet, flute, or any other band instrument.

-Written by Gary Ewer